Silenus the Wise

Father of the Satyrs

Silenus, (Greek: Σειληνος, Σιληνος: Seilênos, Silênos) comes from an immensely ancient and rustic time when gods, nymphs, and mortals were simpler and better rooted in nature. He is famous in mythology for being the adopted father of Dionysos, whom he and the Hyedes, the rain-making nymphs, nurtured in a sweet-smelling cave on the mythical Mount Nysa (See note below on Nysa). He is also known for being the father of the Satyrs who formed part of the Bacchic throng which followed Dionysos.

Silenus’ beard and large, donkey-like ears would have been fragrant with the scent of styrax, the incense burned in the Dionysian cave. Known as a formidable dancer and truthsayer, Silenus’ belly was always full of the wine he taught humans to make.

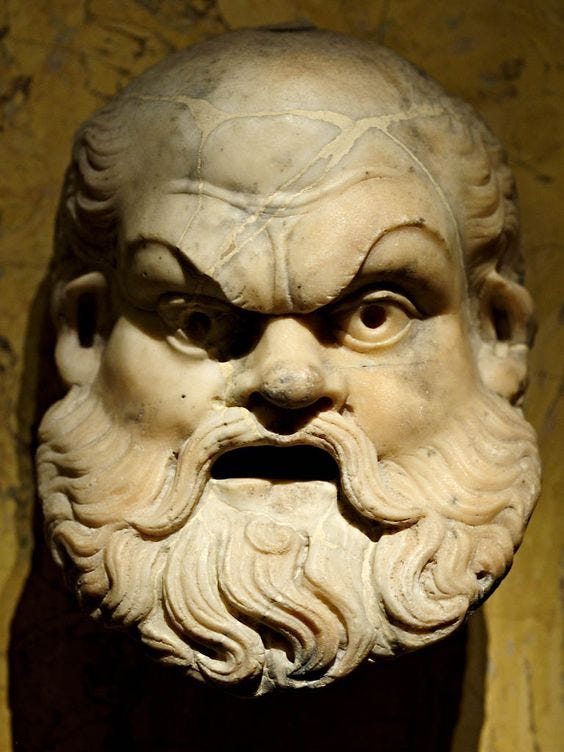

Although Silenus is featured in thousands of pieces of art, minted on coins, carved upon sarcophagi, and strikes the image of mirth and inebriation in paintings and theatre masks, his piercing wisdom is remembered in precious few literary sources.

From Nonnus, the author of the epic Dionysiaca, we know that Silenus was an autokhthon, that is to say, a being that springs fully formed and of its own accord from the Earth. He wrote: “Shaggyhaired Silenus, who himself sprang up out of mother Gaia unbegotten and self-delivered.”[1] Myths place Silenus’ birth and early life in the rugged mountains of Malea, on the southeastern extreme of the Peloponnese.[2]

Over the centuries, Silenus’ appearance shifted, but he is usually depicted as an old man with big ears, hairy legs, and something of a paunch. In the retinue (thiasos) of Dionysos, he is often seen riding a jackass or a donkey, or walking in a drunken stupor between two satyrs. It was when Silenus would become filled with wine that his great wisdom and potent prophetic powers would emerge.

Several ancient sources tell us that while traveling with Dionysos through Phrygia, Silenus got lost in the wilderness. Ovid’s Metamorphoses tells us:

"[Dionysos] made for the slopes and vineyards of his own beloved Tmolus and Pactolus' banks, though at that time the river did not flow golden nor envied for its precious sands. Around him thronged his usual company, Satyri (Satyrs) and Bacchae, but Silenus was missing. For the peasants of Phryges (Phrygia) had caught the old man, tottering along muddled with wine and years, and crowned his head with country flowers and brought him to their king, Midas, whom Orpheus Thracius (the Thracian) and Eumolpus Cecropius once had taught the Bacchic rites.”

In a fragment of Eudemus (354 BCE) by Aristotle, which appears in Plutarch’s, Moralia we see some of Silenus’ wisdom as he reluctantly speaks with King Midas:

“Pertinently to this they say that Midas, after hunting, asked his captive Silenus somewhat urgently, what was the most desirable thing among humankind. At first he could offer no response, and was obstinately silent. At length, when Midas would not stop plaguing him, he erupted with these words, though very unwillingly: 'you, seed of an evil genius and precarious offspring of hard fortune, whose life is but for a day, why do you compel me to tell you those things of which it is better you should remain ignorant? For he lives with the least worry who knows not his misfortune; but for humans, the best for them is not to be born at all, not to partake of nature's excellence; not to be is best, for both sexes. This should be our choice, if choice we have; and the next to this is, when we are born, to die as soon as we can.' It is plain therefore, that he declared the condition of the dead to be better than that of the living.”

As thanks for treating his adopted father well, Dionysos gave Midas the golden touch. What he did with it was Midas’ problem.

Although Silenus became a jolly old stock character known as “Papposilenos” in many an ancient play, we see by Ovid’s story that this wine-tippling old donkey-eared father of the Satyrs shared more in common with Theognis , Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer, than some pithy boozer.

The cult of Silenus was popular at Athens and around the classical world. Statues and shrines built to honor him are dotted about the ancient landscapes of Greece and the Roman empire.

***

[1] Nonnus, Dionysiaca 29. 243

[2] Pausanias, Description of Greece 3. 25. 2 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue 2nd c. CE)

Note on Mount Nysa: Nysa is the subject of speculation. Greek mythographers have placed it in Ethiopia, Libya, Boeotia, Thrace, India, or Arabia. Sir William Jones opined that Nysa was Mount Meru (Sanskrit/Pali: मेरु), also known as Sumeru, Sineru, or Mahāmeru, the sacred five-peaked mountain of Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist cosmology and is considered to be the center of all the physical, metaphysical, and spiritual universes. Meru is near the city of Naishada or Nysa, called by the Greek geographers Dionysopolis.