The Labors of Hercules

A Tale of Redemption & Divinization

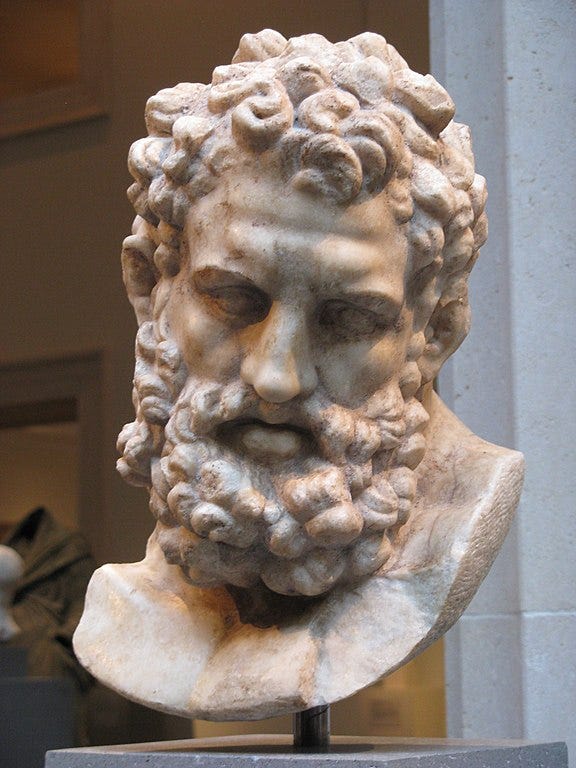

When we think of Hercules it is often his strength that comes to mind, but I think after closer inspection, we will come to appreciate his life and travails in a different light. Strength of character, attention to what is right, insanity, anger, failure, and divine heroic redemption, are all part of his path. Hercules is famous for being a strong man, an amazing hunter, a warrior in the Gigantomachy, and one of the Argonauts who successfully retrieved the Golden Fleece in Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica.

Not many folks realize, however, that Hercules (Greek: Ἡρακλῆς, Herakles; Latin: Hercules) takes his name from Hera (Latin: Juno), under whom he suffered a terrible career of persecution owing to the fact that her husband/brother, Zeus, fathered Hercules with the mortal queen Alcmene of Troezen, in the northeastern Peloponnese. The name Hercules means “glory or fame of Hera”, and his heroic life was much hindered by Hera’s jealous machinations. You can certainly appreciate the irony of the name, given the fact that Hera attempted to kill, maim, and temporarily succeeded in driving Hercules mad, resulting in the slaughter of his wife and family.

Beyond the bitter irony and jealousy we see in these myths, there is also a pattern of important life lessons and tasks which are at once heroic and reminiscent of the struggles of mortals, and then again, initiatory and transcendent. Xenophon tells us that as a youth, Hercules was visited by the allegorical figures of “Vice” and “Virtue”, who asked him if he wanted an easy, comfortable life, or a heroic one.[1] You can guess which one he elected.

Regardless of the rocky path he chose, Hercules was a demi-god, son of Zeus and a divine hero who ascends from the depths of rejection, anger, and madness. He exemplifies courage, virtue, erotic prowess with both sexes, and a fierce, and bright-eyed champion.

At Hera’s instigation, Hercules was driven mad to the point of murdering of his own wife Megara, princess of Thebes, and their many children. After having regained his sanity, Hercules then enters into a very interesting series of initiatory rites. First, he was officially purified of murdering his family by the legendary founder and king of Thespiae in Boeotia.[2] As a symbol of his virility, and after killing a lion as instructed by king Thespius, he invited Hercules to lie with his 50 daughters, each giving birth after their term to 51 grandsons, forty of whom went on to colonize the island of Sardinia.[3] (You learned it at Classics Tutor first—If you want to find the courageous, sexy descendants of Hercules, book passage to Sardinia.)

Although the epic 7th century BCE poem Heracleia (Ἡράκλεια) by Peisander, has been lost since Late Antiquity, we know that it was considered by the ancient Greeks as an important source for the myth of the twelve labors.[4] Much of what we have regarding the labors comes to us from Apollodorus who was writing in the 2nd century CE.

Still another commentary, by the 1st century CE Heraclitus the Grammarian, gave us reason to believe that each of the labors is an allegorical device to show another step in the initiation of Hercules leading up to his deification. This is somewhat reminiscent of the so-called “Great Work” of the alchemists. After having been purified by king Thespius, Hercules goes to Delphi and asks Apollo for guidance, healing, wisdom, and prophecy.

The Oracle instructs Hercules to seek out Eurystheus, king of Tiryns, and do his bidding in order to atone for murdering his wife and family. Originally thought to be 10 tasks, two were added, according to some myths, because Hercules had help with one task, and accepted payment for another, thus nullifying them.

Meanwhile, Hera has not forgotten this son of Zeus by another mother, and suggests 12 impossible tasks to Eurystheus which would surely get rid of Hercules for good. Instead, in my analysis, each successive labor marks another step in the divinization of Hercules.[5]

Beginning with the slaying of the Nemean lion, Hercules shows not only strength, but forethought and restraint in his approach to the indefatigable feline whose hide was like armor. After tricking the lion in the dark of his lair, Hercules strangles him and, with the help of Athena, managed to claim the magical pelt which he henceforth wore to protect himself.

In the second labor, Hercules manages a very delicate situation and slays the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra. After dispatching the monster, he took its venom to poison his arrows. Heraclitus wrote that “the many-headed hydra that he burned, as it were, with the fires of exhortation, is pleasure, which begins to grow again as soon as it is cut out.”[6]

By capturing the Ceryneian Hind, the golden horned and bronze hoofed deer sacred to Artemis/Diana, Heraclitus tells us that Hercules expelled fearfulness from the world, in the shape of the Golden Hind. Any normal person would have been frightened to take the hind because it was sacred to Artemis. Cleverly, Hercules overcame his fear and took the deer on his back, not hurting it. He then explained to Artemis and Apollo that he was not taking the deer for himself, but as a task in servitude to King Eurystheus. The gods agreed to let Hercules take the deer, so long as it would be returned unharmed.

Eurystheus then commanded Hercules to bring him the apparently infamous wild boar which dwelt on Mount Erymanthos. This labor is curious because Heraclitus reckons this to be about overcoming the “common incontinence of men.” I believe this idea comes from the story, in which Hercules goes to the mountain with his friend, the centaur Pholos. The two found a cave where they sat by a fire, ate and drank wine. Meanwhile, other centaurs were attracted by the smell of roasting meat and mirth-giving wine. Unfortunately, things got ugly, and Hercules had to kill the centaurs using his poisoned arrows. Picking one of the arrows up, Pholos mused at how deadly the arrows were, and promptly dropped one on his foot, killing himself instantly. Hercules mourned his centaur friend, buried him, and then went right on hunting the boar. In this sense, Hercules was able to maintain a clear head and keep to his mission, which he accomplished by chasing the boar into deep snow, and then catching him with a net.

From here onward, the tasks get increasingly bizarre. Eurystheus demands that Hercules shovel out the Augean stables in a single day. Mind you, according to the myth, there were a thousand cattle in those fabled stables. That’s a lot of poo to shovel in one day. Here, Hercules makes a little error because he tells the king that he will shovel it out in one day for a tithe (10%) of the cattle. Eurystheus agrees, and as usual, Hercules is successful. But…he took payment for doing the task, and thus another task would have to be done in its place. Heraclitus opines that by shoveling all this dung, Hercules was cleaning “the foulness that disfigures humanity.”[7]

By chasing the deadly Stymphalian birds and shooting them with his arrows, Heraclitus says that Hercules was scattering “the windy hopes that feed our lives.” I think this theory might be reaching a little, but that is what Heraclitus wrote.

I doubt that King Eurystheus reimbursed him for travel, but nonetheless, Hercules voyaged all the way to the island of Crete to capture the Cretan Bull who was terrorizing the city. First, he got permission from King Minos, and then Hercules proceeded to capture the bull. Heraclitus theorizes that “by fettering irrational passions [Hercules] gave rise to the belief that he had fettered the violent bull.”

Traveling over 600 miles northeast of Crete, Eurystheus then sent Hercules to Thrace in order to steal the Mares of Diomedes. As the legend goes, Diomedes, the king of Thrace, trained his mares to feast on human flesh. On this mission, Hercules brought with him one of his lover-companions, a young man named Abderus who was the son of Hermes, or Poseidon, and a mortal woman. Unfortunately for Abderus, while he and Hercules were capturing the man-eating mares, he was eaten himself by the hungry horses. Hercules was obviously devastated.[8] After killing King Diomedes by feeding him to the lethal horses, Hercules made his companion a proper tomb, and founded the city of Abdera nearby to honor his fallen eromenos. All in a day’s work for our hero Hercules.

At this point the labors move from the bizarre to the surreal. After that harrowing experience with the flesh-eating mares, Eurystheus asks that Hercules obtain the girdle or leather belt of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons. At first, Hercules was upfront with Hippolyta, telling her that he had traveled to her lands to fetch her leather girdle for Eurystheus. He may have also muttered under his breath something about how he was pig sick of these every increasingly ridiculous labors, but we just have to leave that to our imaginations. Just when you thought the matter was closed, Hera pops by dressed as an Amazon, and proceeds to lie her face off about how Hercules was actually there to abduct Hippolyta. I think you can guess that, once again, the situation goes south and Hercules ends up killing everyone, taking the girdle, and going back to the court of Eurystheus.

At this crossroads in the labors, we can easily imagine that Eurystheus is hard-pressed for ideas, but he just happened to know that the three-bodied giant Geryon had some cattle that needed rustling. Our friend Heraclitus the Grammarian did not even bother to mention this labor in his work, that’s how surreal it is. Anyway, our hero traveled all the way to the island of Erytheia just off the southern tip of Hispania (Spain), where he was successful in stealing the cattle of the giant, Geryon. After all this travel and work, Hercules returns to Eurystheus’ court and presents him with the cattle. Infuriatingly, the king then proceeds to slaughter the cattle and offer them as a sacrifice to—you guessed it—Hera. Wow, talk about a toxic work environment, but Hercules keeps his cool because he knows this circus has got to come to an end sooner or later.

You might remember, if your mind hasn’t been completely numbed by these carnivalesque labors, that Hercules lost credit for two of the tasks. To make up for them, Eurystheus really pushes his luck and asks Hercules to go back to the Hesperides (Yes, all the way back to Spain), and steal three golden apples. We cannot blame Hercules for being a little peevish at this point, but off he went looking for the golden apples, when he ran into his friend Prometheus, whom he had saved from the eternal punishment of having his liver eaten every day by an eagle. Prometheus tells Hercules that Atlas would be able to easily steal the apples, whereupon Hercules successfully approaches the Titan who holds up the world. It is important to remember that cunning was seen as a positive attribute in the ancient world. And cunning Hercules was as he offered to hold the world for Atlas while the latter went golden apple picking. Atlas tried to trick Hercules, stating that he would steal the apples if he could deliver them to king Eurystheus himself. Hercules agreed. But after coming back with the apples, Hercules asked Atlas if he could hold the world for a minute while he adjusted his clothing. A bit naughty, but, hey, Titans are no angels, either. Hercules picks up the apples and skips all the way back to Eurystheus.

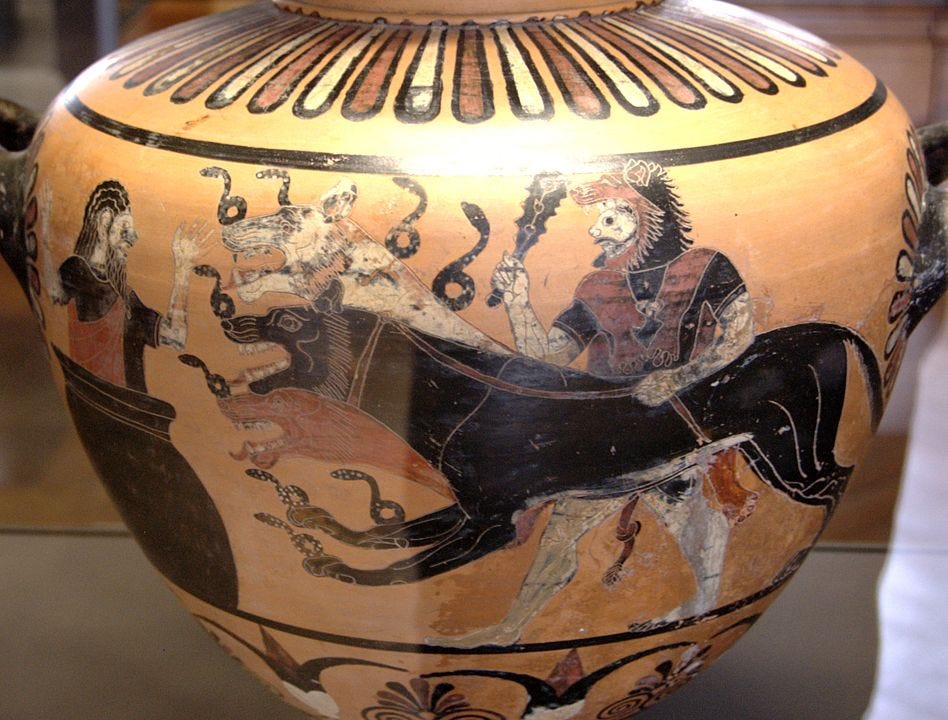

The twelfth labor is a doozy. Eurystheus was getting desperate because he probably knew that Hera was not pleased that our hero had survived and successfully accomplished all of these impossible tasks. Now, Eurystheus sends Hercules to the underworld, where he has to battle a bunch of fierce beasts to make his way to Hades and take his three-headed dog, Cerberus. Not surprisingly, Hercules is able to get Hades’ permission to take the dog, and he returns to Eurystheus. Here, most of us would probably crack and tell Eurystheus to take his labors and shove them where the sun doesn’t shine, but our hero is exactly that—a divine hero. The king demands that Hercules return to the underworld and give the dog back to Hades. The words “go to hell” come to mind. You will not be surprised to learn that Hercules accomplishes the last part of his 12 labors successfully.

Some myths say that after stumping Hera and Eurystheus, Hercules was bored and joined the crew of the Argo and went off on the famous adventures with Jason to find the Golden Fleece. You can read that myth in the Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius.

As for the apotheosis of our hero, after showing himself worthy, and learning to control his passions and thoughts, Hercules is sadly killed by a poisoned garment. Writhing in agony, Hercules ripped up some trees, made a pyre, and asked his friend to light it. Ovid tells us that as his body is burned, the mortal part of him is burned away, and Zeus takes his immortal side to Olympus where he is made into a god.[9]

The cult of Hercules was widespread in Greece, Asia Minor, Sicily and on the Italian peninsula, as well as in Egypt, the Levant, and North Africa. Because of the spread of Hellenistic beliefs under Alexander the Great, there is also evidence of the cult of Hercules in places like India, Iran, and Afghanistan.[10]

The central theme of the Herculean cult is his role as divine protector of humanity. In this sense, the labors illustrate his ascendancy into that role, culminating in his deification.

Whew, this post has been a Herculean labor in itself! I hope you enjoyed it. See you next time!

***

[1] Xenophon, Memorabilia 2.1.21–34

[2] Apollodorus, 2.4.10

[3] Diodorus Siculus, 4.29.1 & 4–6

[4] Brill's New Pauly, s.v. Peisander (6) NB: In Heracleia, there are thought to have been only 10 labors, the last two having been added by other traditions.

[5] Heraclitus. Homeric Problems, 33

[6] Ibid, Heraclitus, 33

[7] Heraclitus, 33

[8] Pseudo-Scymnos, Circuit de la terre 646 ff.

[9] Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book IX.

[10] See: Bijan Omrani, “The Greeks, Afghanistan and the Buddha”, Antigone.

Do you have any thoughts on the theory that places Herakles' real inspiration into the neolithic age? (For example, Nemean lion being a cave lion and similar)

Yes, there is significant truth to this theory, and it is supported by two distinct but complementary fields of study: evolutionary mythology (how oral traditions preserve deep history) and geomythology (how ancient people interpreted fossil evidence).

Scholars essentially argue that Herakles is a "composite" figure whose most primitive traits—his club, his lion skin, and his mastery over wild beasts—are fossilized remnants of a much older Neolithic or even Paleolithic past.